How to amplify a gigging Gypsy jazz band

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. (Albert Einstein)

There's always an easy solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong. (H. L. Mencken)

Huh? What have these quotes got to do with how we amplify the musical instruments — currently acoustic violin, acoustic guitar, and fretless bass — which FiddleBop uses to play “Jazz-folk” at live gigs? Everything, as it turns out. Our mostly trial-and-error experiences have helped us to get a good live sound for FiddleBop. With a setup that is as reliable and simple as we can get it. But not too simple (ho ho!).

So I’ve written this summary in the hope that it may be useful to others. Just as I hope that the "Is it OK to call this music 'Gypsy jazz'?" discussion might be useful.

If anything isn't clear, or if you disagree with what I say, or if you would like more information, then email me at info@fiddlebop.org. Good luck with getting your own music amplified just as you would like it!

Amplification in the past

Being heard properly was a major problem faced by the originators of Gypsy jazz, Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli in the Quintette du Hot Club de France back in the 1930s. Jazz bands of that time mostly consisted of brass instruments, Which are LOUD. Acoustic (un-amplified) violins and guitars just can’t produce the same sort of volume. So Django and Stephane and the band, unamplified, would have been easily overwhelmed aurally by any lively and chatty Parisian audience. Swing-era dancers would have drowned out the band, no question.

Fortunately, microphones were becoming common in venues around this time. This rise of microphone-based live amplification was a game-changer for early Gypsy jazz. OK, there might only have been one microphone shared by the whole band, but that would have been a great deal better than nothing.

At around the same time over in the US, jazz violinists Joe Venuti and the wonderful Stuff Smith were experimenting with the first electrically amplified violins. And a few years later on, Django began playing guitars with electric pickups.

Amplification now

The need for relatively quiet instruments to be heard over background noise in live venues is still with us in 2025, nearly a century after the Quintette of the Hot Club de France. Also, audience expectations have risen: the quality of live sound is now expected to be similar to that of a studio recording.

OK, technological advances in audio engineering during this century have been immense. So why isn’t it a piece of cake (or a walk in the park) to get a good live sound for FiddleBop’s instruments[1]? Using equipment that is quick and easy to set up, and which works reliably?

Let’s take one instrument at a time.

Amplifying an acoustic nylon-string rhythm guitar

FiddleBop, like most gypsy jazz bands, does not have a drummer or percussionist. This means that we are totally, 100%, reliant on Jo’s rhythm guitar playing to keep us in time. (Not for nothing do we say that “Jo is the rhythmic foundation of FiddleBop”.) If we can’t clearly hear her guitar's rhythm, we can’t play well as a band. This could be a problem, given that some FiddleBop numbers verge on being both fast and rhythmically intricate 😃.

Which is why amplifying Jo’s nylon-string guitar is the most important thing that we have to do, live sound-wise. Both for the band’s ability to play decently, and to ensure that Jo’s contribution to the overall FiddleBop sound is as good as it possibly can be. Easy? Nope.

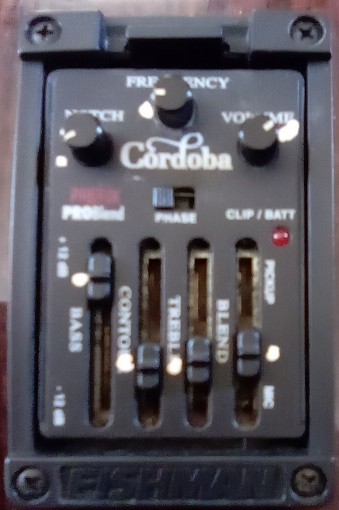

Jo plays a Cordoba Gipsy Kings Pro Negra nylon-string (“Spanish”) guitar[2]. It is fitted with a Fishman Pro Blend pre-amplifier, which has two sound sources: an under-bridge piezo, and an internal microphone. These can be blended, as the pre-amp's name suggests. Jo has found, tho’, that for her playing style the best sound comes almost wholly from the internal microphone. Which is great, but which makes the guitar liable to generate feedback if the guitar's amplified sound enters the guitar’s soundhole i.e. comes from the front of the stage back towards Jo. Feedback is less of a problem if amplification is at the rear of the guitar i.e. from a backline amplifier behind Jo. Which means that monitoring of Jo’s guitar from the front of the stage, back towards the band, is a no-no for us.

There’s more. Jo sometimes strums her guitar, at other times she uses fingerstyle picking. Each of these requires a notably different EQ and volume setting. She swaps between these settings by means of an Artec footswitch on her pedalboard, which switches her guitar’s output to one or other of the two channels of her Headway Shire King 60 backline amp. Each channel on the Headway has a different EQ and volume setting. The amplified output from her Headway comes from these two channels (only one of which is in use at any time, however.)

The Headway SK-60 is always positioned behind Jo, and it functions as a monitor both for Jo and for the rest of the band. And if we are playing in anything but a tiny venue, the Headway’s Effects Out signal (both channels, post-EQ but not affected by the Headway's master volume control) goes to a mono DI box (a Behringer Ultra DI 100) which then routes Jo’s guitar sound to one channel of the front-of-house PA system.

Amplifying an acoustic violin

Dave's well-used acoustic violin is (probably) German, (probably) about 100 years old. I have owned it for many years[3]. During Covid lockdown — what else was there to do? Apart from walk on our beautiful hill, of course — Richard (aka Titch) of Sonic Violins installed a piezo bridge and an internal battery-driven pre-amplifier. This works well. But as with any amplified acoustic instrument, the violin can still generate feedback if it picks up its own amplified sound. So I avoid in-front monitoring i.e. sound which comes from the front of the stage back towards me. Instead I — and the rest of the band — rely on hearing my violin's sound from my Headway Shire King 60 backline amplifier. Which, like Jo's backline amp, is positioned behind me.

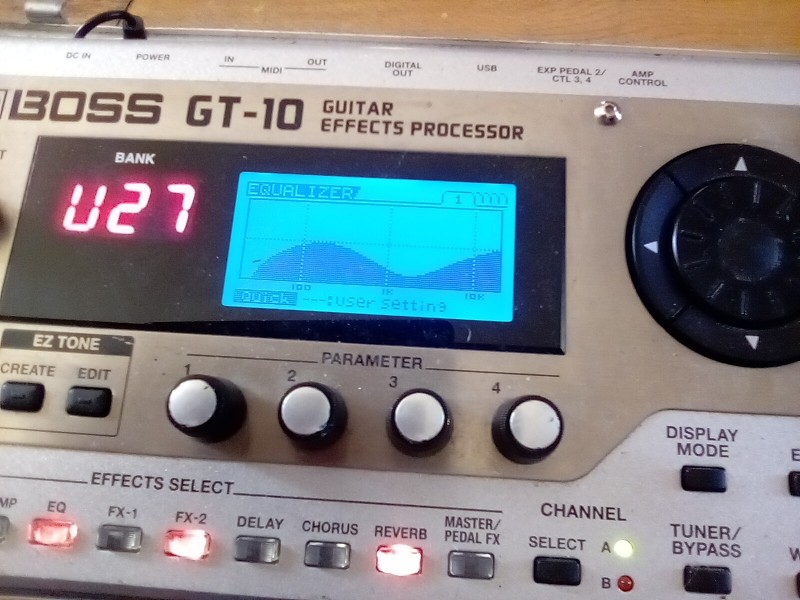

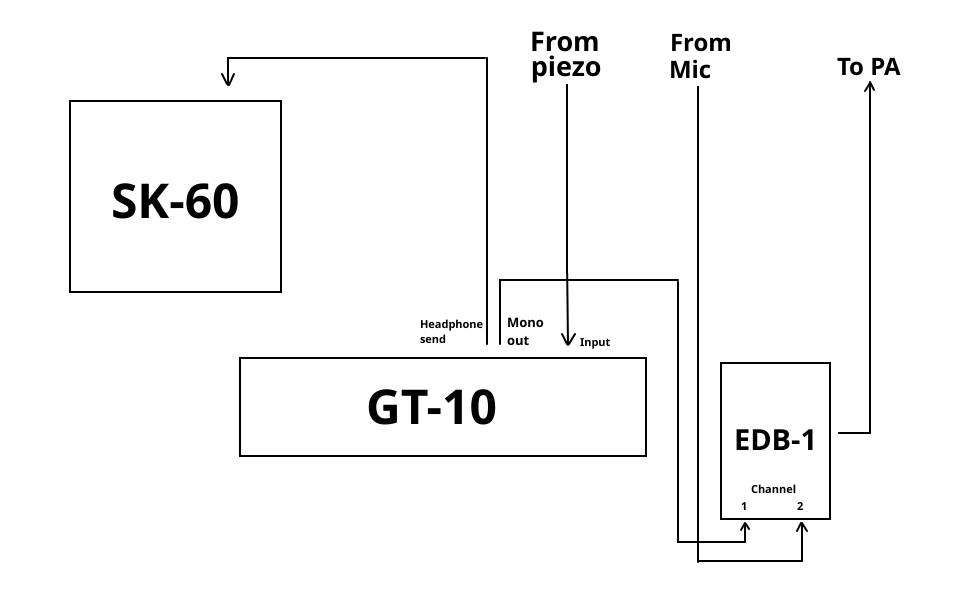

As with any piezo pickup, there is a need to remove “piezo quack” (Google it!) at around 1.2 kHz or thereabouts. I do this with the EQ wizardry in my Boss GT-10 effects unit. A mono output from the GT-10 (I use the headphone output jack socket for this) goes to Channel 1 of a Headway EDB-1 pre-amplifier (this model is now discontinued).

That's just half of the story. Why? Because good as the piezo pickup is, it still does not have the sound quality of a microphone. So in parallel with the bridge piezo, I also use a Behringer CB100 condenser gooseneck microphone mounted on my violin. It sounds great, but is prone to feedback. Much more so than the piezo pickup. So, how to avoid this?

The approach that I take is to send only the mic output to the front-of-house PA. So the CB100 mic is connected to Channel 2 of the Headway EDB-1 pre-amplifier, which also supplies the phantom power needed by the CB100. The merged piezo-and-mic outout from the EDB-1 goes to the PA via a mono DI box (again, a Behringer Ultra DI 100).

So one channel of the front-of-house PA system receives a blend of the piezo and mic signals from my violin, while the SK-60 backline amp receives only the piezo signal.

This isn't perfect (I only get to hear the piezo output), but the arrangement is pretty much feedback-free.

Fretless electric bass amplification

However the amplification setup for Graeme's solid electric fretless bass is also straightforward. Hooray!

The bass is by Lamble Guitars: Graeme made it himself (isn't he clever?). The melodious sound of this bass reaches all our ears by means of ar Behringer B210D monitor, used as a backline amplifier. It is normally positioned just behind Graeme.

Bass sound goes to the front-of-house PA via a Behringer Ultra DI 100, which is connected between the bass and the B210D monitor.

Summary and more

Yup, amplification for FiddleBop ranges from “easy and straightforward” for the bass; through “reasonably easy” for the violin; all the way through to “rather difficult” for the guitar. It has taken some time and experimentation to get our setup working well, but it was — for sure! — worth the effort. Probably it would have been even trickier if we had a drummer: since we don't, we can keep sound levels low on stage, and so minimize the risk of feedback from the acoustic instruments.

I've touched on the desirability of a "quick and easy" pre-gig set up for our amplification, but haven't said much about this. We've found that marking the correct position of each knob or slider (in other words, the position that we've settled on after hours and hours of experimentation, by which time our ears have gone numb) with a dob of correction fluid — one brand being Tippex — is a great time-saver. One glance and you are done (see the pics of Jo's pre-amp and amp, above). And it is easy enough to scrape off the dob if we later change your mind about the optimum position.

Another thing that helps greatly with the speed of pre-gig setup is having colour-coded cables. We also stick matching coloured dots close to connectors and sockets to quickly show us what goes where (see the pics of Jo's amp and pedalboard above). This helps with the "reliable" goal too: if, when we've set up, we find that something doesn't work, the chances are high that it is a cable problem. Having colour-coded cables makes it easy to identify the problem cable, so that we can then replace it with a backup.

We also mark all FiddleBop's cables and equipment with pink coloured electrical tape. It is surprising how easy it is to leave one of our own cables behind, or pick up someone else's by mistake, in the chaos of post-gig packing up.

By the way, the various makes and models of equipment mentioned here are just our choices. We like 'em but you might well choose something different. No problem 😃.

That's it! I hope that this is useful to someone, somewhere, sometime. Good luck with your music, and thanks for reading this far!

- I’m not going to discuss amplifying vocals here. This essay is already too long! ↩

- Interestingly — considering Jo's style of playing — Cordoba describe this as a flamenco-style guitar. We've found it to be a bit brighter, and more percussive, than most classical guitars. ↩

- And almost ruined it with superglue. Don’t ask... ↩

- We've found that we have to cut the bass on the keyboard monitor, to avoid frequency overlap with Graeme's bass. ↩

info@fiddlebop.org

info@fiddlebop.org 01982 560726

01982 560726 Site map

Site map @FiddleBop

@FiddleBop @fiddlebop

@fiddlebop @FiddleBop

@FiddleBop Get our email newsletter

Get our email newsletter